by Virginia Castlen Vertiz

There was magic in having turned eighteen just prior to the Summer of Love, especially since we lived less than three miles from Georgetown and nearby Dupont Circle. New friends included hippies traveling back and forth from Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco, local band members playing in favorite clubs, and famous musicians visiting Washington. Everyone conversed and mingled before and after concerts. Clothing styles were not far behind those of the Mod subculture that had begun in London and spread throughout the United Kingdom in the mid-sixties. Life in the fifties and early sixties had been black and white.

Valedictorian in kindergarten, my grades slid throughout public school and early college. After the devastating departure of my greatest advocate, my father, just after my fifteenth birthday, my mother purchased a color television. The appearance of The Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show jettisoned me from Beatnik leanings to a kaleidoscope of other possibilities.

I abandoned the conformity of the preppy collegiate clothing that the prominent high school clique wore and found myself in the company of the coolest girl in school, Linda Sue Dawley (LSD!) She had rejected conformity, and her long, silky light brown hair, straight bangs, and high, brown suede boots were reminiscent of Pattie Boyd and other famous British models. Back then, I went by “Gini.”

For my early March birthday, I really wanted a sports car, but Mother insisted that I buy her Mercury Comet instead. I brightened its dull beige with multi-colored flowers cut from sticky plastic, leftovers from an art project that Linda and I were paid to do. Having a car enabled me to go to Georgetown and Dupont Circle and take my friends along.

I loved going to the Corral, a bar and band venue with another club, the Frog, downstairs. The dance floor was in a bay window. I could dance all night to my favorite bands right there on M Street: first to The English Setters, who changed their name to The Cherry People, and then to The Mosaic Virus, originally called Elizabeth Fagot’s Revenge. Lead guitarist and special friend Edwin Lionel Meadows, “Punky,” went on to form Angel, which created quite a sensation on the West Coast.

After I returned from a June/July trip to Europe with my mother, The Mosaic Virus had become the house band at the Ambassador Theater in nearby Adams Morgan. Their drummer, William “Duke” Ayres, told me that their band wouldn’t be playing the second week of August, because Jimi Hendrix had been kicked off The Monkees’ tour and would play that week instead. Duke invited me to go with him, and we went all five nights that Hendrix was there: August 9th to the 13th.

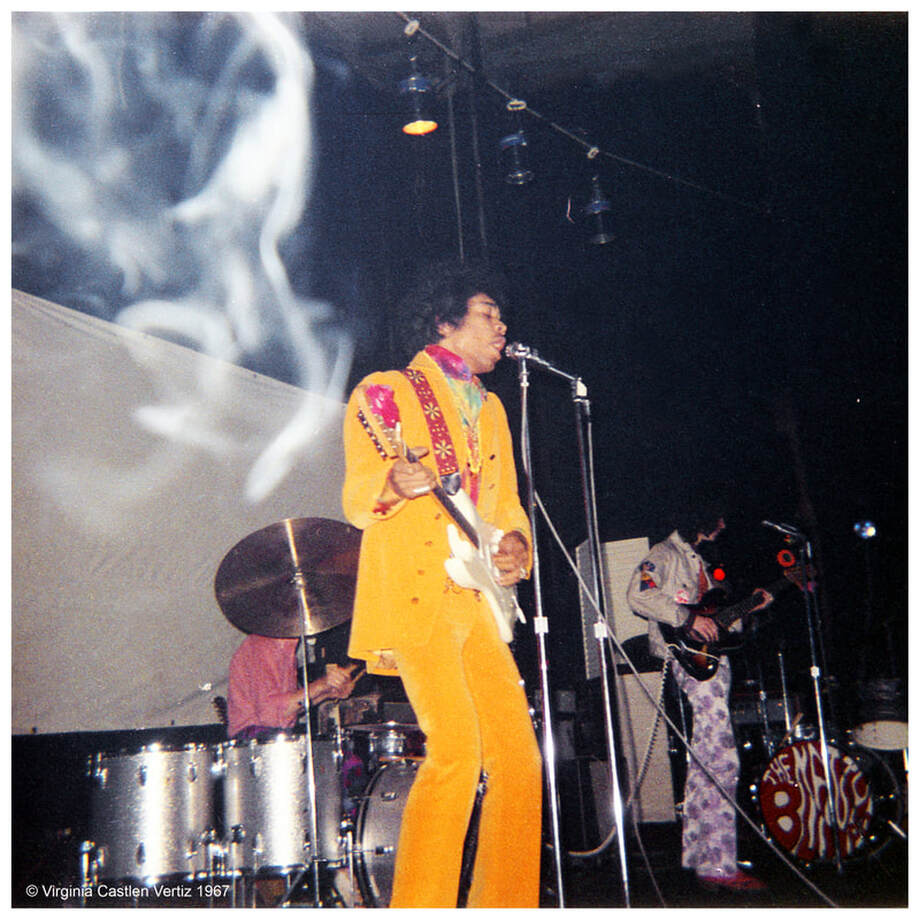

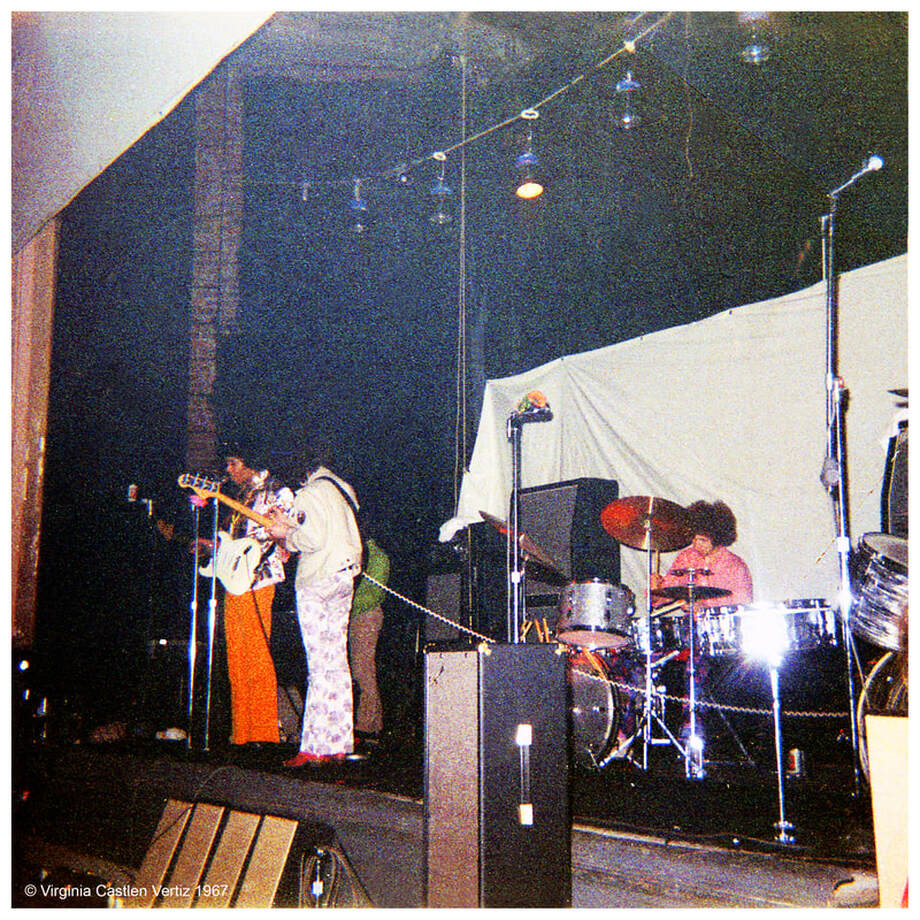

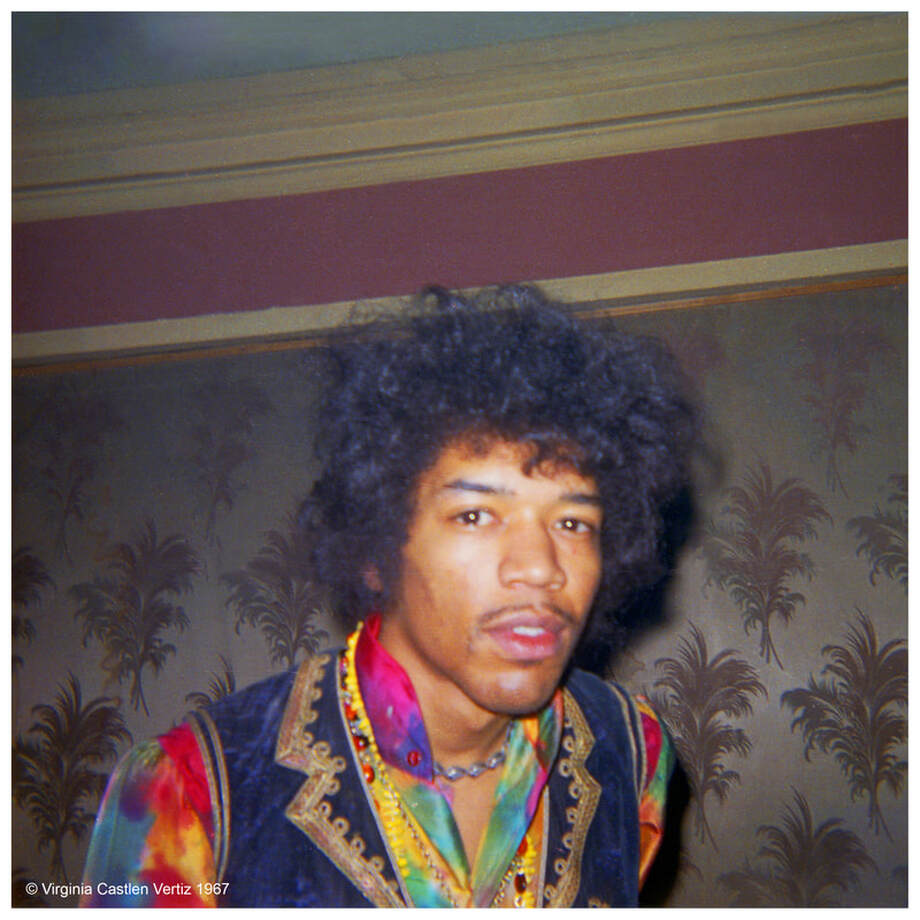

The cultural revolution was well underway. If the Beatles woke us up, Hendrix shook us up. His lavish, colorful clothing, left-handed playing of a right-handed guitar, smoke streaming from a cigarette impaled on one of his guitar strings—it all presented a sharp contrast to his humble, quiet demeanor. And as if his mind-blowing mastery of the guitar, his original compositions, and his new arrangements weren’t enough, he played the guitar behind his back and with his teeth, with apparent equal ease.

Valedictorian in kindergarten, my grades slid throughout public school and early college. After the devastating departure of my greatest advocate, my father, just after my fifteenth birthday, my mother purchased a color television. The appearance of The Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show jettisoned me from Beatnik leanings to a kaleidoscope of other possibilities.

I abandoned the conformity of the preppy collegiate clothing that the prominent high school clique wore and found myself in the company of the coolest girl in school, Linda Sue Dawley (LSD!) She had rejected conformity, and her long, silky light brown hair, straight bangs, and high, brown suede boots were reminiscent of Pattie Boyd and other famous British models. Back then, I went by “Gini.”

For my early March birthday, I really wanted a sports car, but Mother insisted that I buy her Mercury Comet instead. I brightened its dull beige with multi-colored flowers cut from sticky plastic, leftovers from an art project that Linda and I were paid to do. Having a car enabled me to go to Georgetown and Dupont Circle and take my friends along.

I loved going to the Corral, a bar and band venue with another club, the Frog, downstairs. The dance floor was in a bay window. I could dance all night to my favorite bands right there on M Street: first to The English Setters, who changed their name to The Cherry People, and then to The Mosaic Virus, originally called Elizabeth Fagot’s Revenge. Lead guitarist and special friend Edwin Lionel Meadows, “Punky,” went on to form Angel, which created quite a sensation on the West Coast.

After I returned from a June/July trip to Europe with my mother, The Mosaic Virus had become the house band at the Ambassador Theater in nearby Adams Morgan. Their drummer, William “Duke” Ayres, told me that their band wouldn’t be playing the second week of August, because Jimi Hendrix had been kicked off The Monkees’ tour and would play that week instead. Duke invited me to go with him, and we went all five nights that Hendrix was there: August 9th to the 13th.

The cultural revolution was well underway. If the Beatles woke us up, Hendrix shook us up. His lavish, colorful clothing, left-handed playing of a right-handed guitar, smoke streaming from a cigarette impaled on one of his guitar strings—it all presented a sharp contrast to his humble, quiet demeanor. And as if his mind-blowing mastery of the guitar, his original compositions, and his new arrangements weren’t enough, he played the guitar behind his back and with his teeth, with apparent equal ease.

The Ambassador’s huge interior had a wood floor that made for a tremendous sound. Not a studio sound—rather, a reverberation off the walls. A light show projected pure psychedelia all over the stage and in time to the beats. Marijuana and incense seasoned the air. There was no seating. Only about fifty people attended the first night.

At the Ambassador I shadow danced with a friend behind a curtain above The Jimi Hendrix Experience. We also milled around on the floor. Few people carried cameras, and there were no cell phones, much less phones with cameras. I took along a Kodak Instamatic. Film, developing, and printing were expensive, so I shot only four photos of Jimi Hendrix.

At the Ambassador I shadow danced with a friend behind a curtain above The Jimi Hendrix Experience. We also milled around on the floor. Few people carried cameras, and there were no cell phones, much less phones with cameras. I took along a Kodak Instamatic. Film, developing, and printing were expensive, so I shot only four photos of Jimi Hendrix.

The Who were playing at nearby Constitution Hall on the last night, and when they finished, two members came to the Ambassador to see Hendrix. Lead guitarist Pete Townshend stood to my right and bass player John Entwistle to my left. In those few months during the Summer of Love, famous musicians were just other people enjoying the scene. I never thought to ask for autographs, and selfies were a thing of the far-distant future.

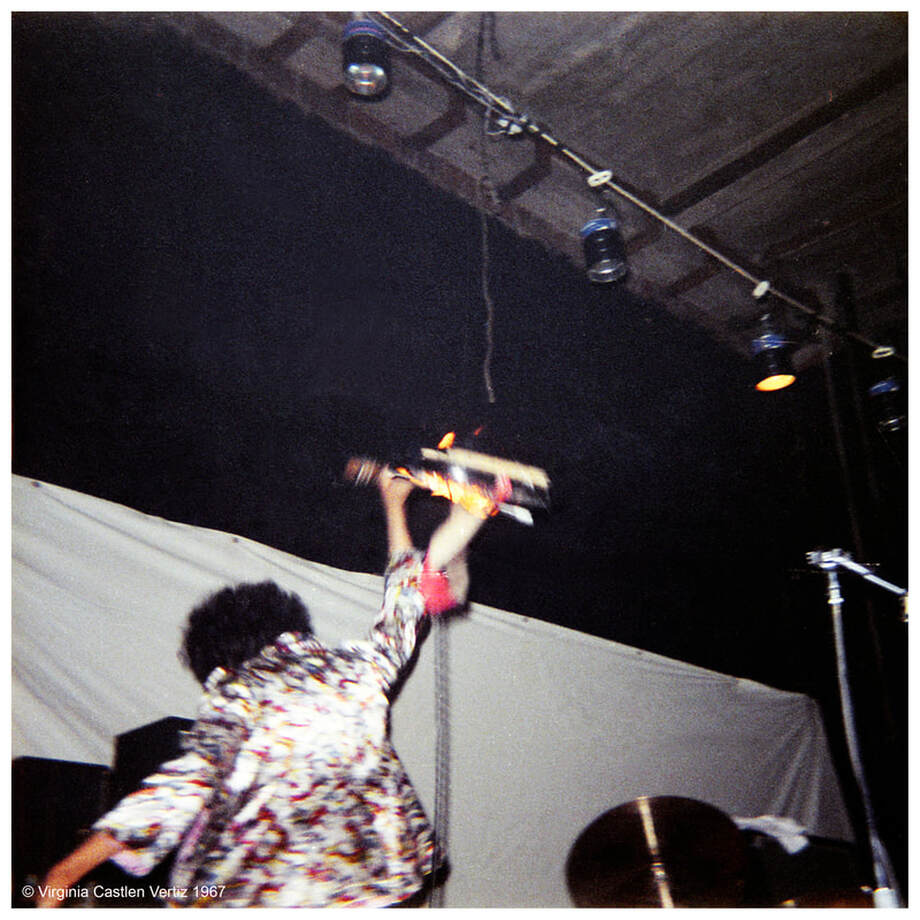

Townshend had begun smashing his guitar into his amplifier, and apparently Hendrix was determined to outdo him. Hendrix had lit his guitar on fire at the London Astoria earlier that year in March and at the Monterey Pop Festival in June. The first time, no pictures were taken, but there is video of the second.

On his last night at the Ambassador, Hendrix placed his guitar at the front of the stage, poured lighter fluid on it, set it on fire, and swung it above his head. Camera ready, I snapped a picture just as he turned to smash it into his amplifier.

Townshend had begun smashing his guitar into his amplifier, and apparently Hendrix was determined to outdo him. Hendrix had lit his guitar on fire at the London Astoria earlier that year in March and at the Monterey Pop Festival in June. The first time, no pictures were taken, but there is video of the second.

On his last night at the Ambassador, Hendrix placed his guitar at the front of the stage, poured lighter fluid on it, set it on fire, and swung it above his head. Camera ready, I snapped a picture just as he turned to smash it into his amplifier.

I didn’t think the pictures I’d taken, including that one, would have any special significance. But Linda told me they would become iconic. I gave her one set and kept the other. Over the years, she showed them to people. They implored her to let them make copies, but she respected my rights and never allowed it.

Word of my photos got around to Jeff Krulik, a DC-based director/producer who was planning an event in 2017, the fiftieth anniversary of the Summer of Love. He contacted me several times about the photos, and I finally agreed to look for them. I had given away a few more copies of the photos to two or three special friends, but I’d digitized most of my media and no longer had hard copies. As the years passed, I wasn’t even positive I’d taken a picture of Hendrix burning his guitar. Linda was certain.

I didn’t respond to Krulik immediately. I had thousands of negatives packed into two shoeboxes. Sorting through them would be a challenge. But Krulik was persistent. If a photo of Hendrix burning his guitar existed, I must still have the negative.

I found it.

I had all four Hendrix negatives printed and was featured on two television shows. Local reporter Mark Segraves came to my house and interviewed me. He also invited me to a local television studio where I talked about the photos. Bill Bentley, the author of Smithsonian Rock and Roll Live and Unseen, said that nobody believed that Hendrix had burned his guitar that week, that it was a local myth. He called my photo “the Holy Grail of lost artifacts.”

Word of my photos got around to Jeff Krulik, a DC-based director/producer who was planning an event in 2017, the fiftieth anniversary of the Summer of Love. He contacted me several times about the photos, and I finally agreed to look for them. I had given away a few more copies of the photos to two or three special friends, but I’d digitized most of my media and no longer had hard copies. As the years passed, I wasn’t even positive I’d taken a picture of Hendrix burning his guitar. Linda was certain.

I didn’t respond to Krulik immediately. I had thousands of negatives packed into two shoeboxes. Sorting through them would be a challenge. But Krulik was persistent. If a photo of Hendrix burning his guitar existed, I must still have the negative.

I found it.

I had all four Hendrix negatives printed and was featured on two television shows. Local reporter Mark Segraves came to my house and interviewed me. He also invited me to a local television studio where I talked about the photos. Bill Bentley, the author of Smithsonian Rock and Roll Live and Unseen, said that nobody believed that Hendrix had burned his guitar that week, that it was a local myth. He called my photo “the Holy Grail of lost artifacts.”

The Ambassador lasted only six months as a concert hall for hippies. We were a small group compared to those in San Francisco, and not enough to support such a large venue. Nevertheless, the Ambassador made a significant contribution to the Summer of Love.

I unveiled my photographs at the Ambassador’s anniversary celebration. I invited Duke, whom I had found in the audience, to join me onstage. Had it not been for him, I wouldn’t have the story to share. And had it not been for Linda, I might not have ventured into the halcyon days of the Summer of Love.

When I met him that summer, Hendrix was soft, sweet, and shy. I was shy as well. I never would have guessed how important those moments would be or how soon he would leave the world.

Hendrix would have turned eighty this year. Coincidentally, he shares my daughter Carrie’s birthday, November 27th. In July of this year, Carrie took my husband and me to Renton, Washington—to Hendrix's gravesite and memorial—so that I could say farewell to the greatest guitarist of all time.

I unveiled my photographs at the Ambassador’s anniversary celebration. I invited Duke, whom I had found in the audience, to join me onstage. Had it not been for him, I wouldn’t have the story to share. And had it not been for Linda, I might not have ventured into the halcyon days of the Summer of Love.

When I met him that summer, Hendrix was soft, sweet, and shy. I was shy as well. I never would have guessed how important those moments would be or how soon he would leave the world.

Hendrix would have turned eighty this year. Coincidentally, he shares my daughter Carrie’s birthday, November 27th. In July of this year, Carrie took my husband and me to Renton, Washington—to Hendrix's gravesite and memorial—so that I could say farewell to the greatest guitarist of all time.

|

Virginia (she/her) has worked as a teacher, social worker, administrator, researcher, editor, and systems consultant, among others. She’s authored many articles, book chapters, and professional papers. Virginia is now turning her attention to genealogy, historical research, and telling personal stories—particularly those of her mother, who was an editor, writer, and aspiring author. Twitter @vcvertiz | Instagram @womanonedge | Facebook @VCVMoomy

|